I want to take a minute to acknowledge a major challenge in taking time off to travel. For me, it was very hard to leave. I felt a great deal of guilt and sadness leaving kids on my Speech team during their high school journey, colleagues who I had built curriculum and relationships with, growing nieces, aging grandmothers, and a city full of close friends. During my final week in New York, I had 2 panic attacks (one of which was on my last day in my classroom). I felt my heart freezing and chest gasping for breath at the prospect of such a huge life shift and of abandoning a job that I had worked so hard to become good at over the last five plus years.

Because I coached Speech after school and on weekends, I generally worked 12 hours a day (+ or -), 7 days a week. My job as a teacher permeated my dreams as well as my waking thoughts. I worked with all my heart to become more equitable, more patient, and more thoughtful in my planning so I could predict and meet all my students’ needs.

While I knew intellectually that this gap year would be an amazing opportunity to learn and explore, and I wanted to approach the departure with excitement and gratitude, I mostly felt like clinging to all I had built in myself and my life at MELS (the Metropolitan Expeditionary Learning School). I had exhausted myself on a climb to high-quality teaching, and I was just about to start seeing the rewarding views!

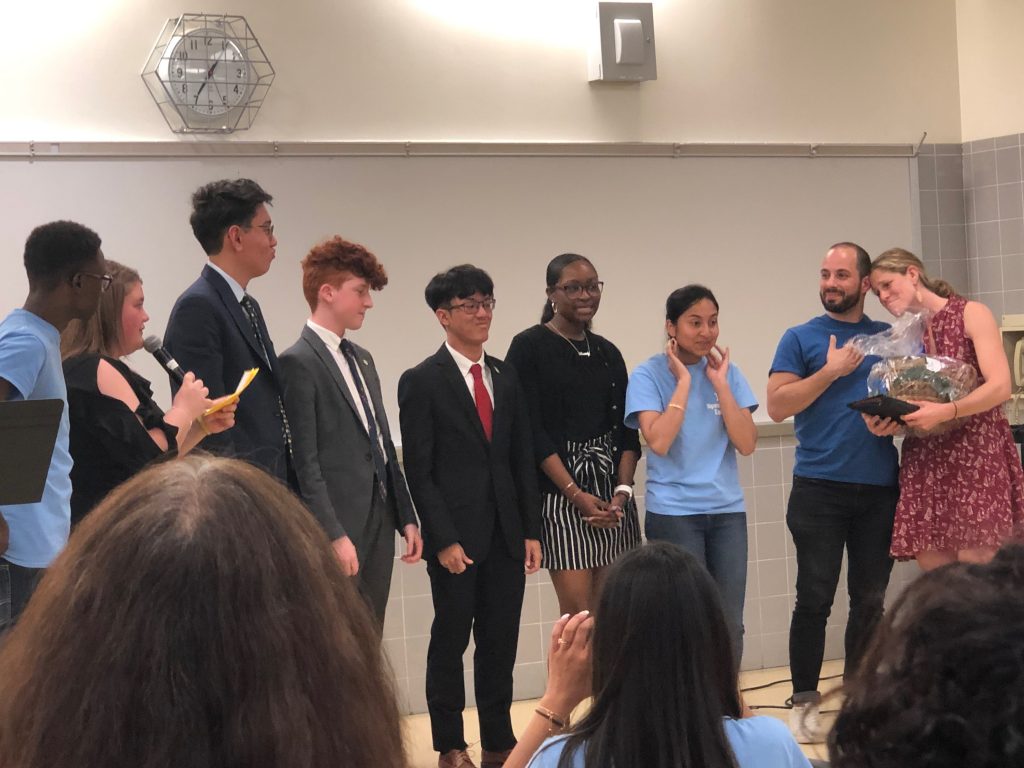

How can you not miss these people!

So, why did I take the leap and quit after all?

It’s not like my husband dragged me on this worldwide adventure kicking and screaming. Victor and I chose to uproot ourselves because we felt the need to do so. As John Muir said, “the mountains are calling and I must go.” For our entire 6 years in New York, I had felt at odds with the city. While I grew more comfortable as we explored New York’s amazing surrounding regions (the Hudson Valley, the Catskills, Round Valley Reservoir in New Jersey, etc), it was always too loud, too fast, and not quite green enough for me to really feel at home.

There were personal reasons, too. We were almost ready to start a family, but weren’t sure where we wanted that to be, and when the clock ran out on our 2011 pact (“no babies in the 20-teens”), we wanted a grand adventure to justify another year’s delay.

And professionally, while the end of the school year always brings feelings of nostalgia and re-casts the year in a rosy gloss, I also knew that I had been bone tired too many times to count. I hated repeating the same lessons and the same instructions (“voices off in 5, 4, 3…”) to 4 classes of 30 students every day. I loved reading student writing, but I hated staying up until midnight on nights, weekends, and vacations in order to give thorough feedback on every assignment to 120 students. I loved some kids like they were family, but was deeply wounded by others–both because of my frustration with my own inadequacy at supporting them and because of their hurtful words and actions. I loved my school’s mission and ethos as well as the intellectual challenge of innovative curriculum design, but I was deeply questioning if I enjoyed teaching enough to persist through the indignities and exhaustion of the struggle. I knew some of my strengths included positive energy, optimism, and diligence, but I wondered what other strengths would be revealed in a different work setting. I also had been in schools my entire life, and was curious to know what other work environments felt like.

These complaints feel selfish to articulate because they are focused on ME, and not my students. It was hard for me to even acknowledge these feelings for a while because of my shame at potentially abandoning teaching and joining the infamous revolving door that shuttles young teachers in and out of low-income communities. However, my complaints were real, and I finally decided to let myself listen to them.

So, leaving was like poking a hole in the space station. I wanted to see what was out there, but instead of jumping to stable ground, I was just floating in space.

I thought my feelings of sadness and guilt at leaving teaching (and specifically MELS) might wane as I travelled around the world, but so far they haven’t. I have certainly felt profound freedoms–to choose what I want to do with each day, to be curious, to use time slowly or quickly at my leisure, to read more, to write more, to spend more time outside, to learn the Bulgarian alphabet! I have also worked hard to be present, putting my phone away and listening to what my surroundings are telling me. I cherish this, and appreciate how much it will seem like a distant memory when we return to work. However, I have also continued to think about my job every day since we left.

A conversation with a dean from the American College of Sofia helped me reframe this feeling a bit, though it certainly still lingers like a bruise on my heart. He was describing his career working in schools across the globe: “We spent a year in Morocco, had a kid and spent 10 years in Connecticut, spent 3 years in China, then 4 years in Jordan, then 3 years in Rome.” I asked him which place was his favorite to work in, and he said that was an impossible question because each phase was so unique and each job incomparable to the previous or the next.

I was awed at his description of his life path. My grandfather built our family business in Baltimore 75 years ago, and my father, uncle, and cousins still work there. I went to the same high school that my mother did. I feel grounded in the place that raised me, and deeply tethered to the professional community I grew up in over the last 5 and a half years. Indeed, it’s the only real place I’ve ever worked (not odd jobs, but day in, day out blood, sweat, and many tears). In speaking with this man, I realized that leaving MELS felt scary and somehow terminal because it was my first professional phase, and I had defined my working self in tandem with its mission.

When the dean spoke of his world-wide professional experience across multiple decades, it reminded me that life is long and there is work to be done everywhere. He spoke about his jobs with such reverence and detail that it was clear he lived each of those roles as deeply as I had committed myself to MELS. Moving on to a new phase is not treachery or selfishness, but a vital part of thoroughly lived life.

So, this sadness and guilt are perhaps just part of the transitional mourning of one phase of life as I enter the next. It is hard to see this phase of learning to be a teacher at MELS as just one era of many because right now it holds such prominence in my professional story. However, taking the long view feels like an important step in understanding that there are many varied opportunities to create change in the world. Leaving wasn’t giving up or abandoning–it was moving on. Maybe I won’t be able to ditch this nagging guilt and sadness until I find the next job to dig my teeth into. Maybe I will actually return to a community like MELS because I imagine it is rare to miss your job so much after quitting to travel the world…

Either way, as my colleague, Claire Wolf, said to me on the last day of school: “you have to keep moving forward; the only other option is death, and moving on is way better than that alternative.”

Leave a reply